The ACU opens up to queer people

From the 70s to the 90s, squatting was crucial for housing in the Netherlands. One of the most well-known former squats in Utrecht is the ACU on Voorstraat 71 in Utrecht, a vibrant place for radical left activism, and today for queer activism and culture as well. But queer people really started to hang out there from 1985, with the introduction of queer disco, on the initiative of PATS, a queer revolutionary fanzine from Utrecht. From the 1990s onwards, the ACU became a major place for queer (radical) activism in Utrecht. It was often the starting and ending point of demonstrations organised by the queer movement.

Originally meaning “strange” or “peculiar” (attested since the 16th century) and later used as a slur for feminine or gay men (from the late 19th century onwards), the word “queer” started to be reclaimed in the 80s, mainly by the activist, revolutionary side of the community. Nowadays it is also an alternative for LGBTQIA+.

The squatting movement as a “white male stronghold”

Queer people were not massively present in the squatting movement. Specifically, during its booming years in the 1980s, the left-radical squatting movement was very masculine and heterosexual, where sexism was common. Marga Sutherland, a then queer activist who participated in the squatting movement in Utrecht in the 80s and 90s, including actions for gay and lesbian emancipation, recalls the squatting movement as “a white male stronghold”, a partly macho movement, where sexism was very much alive, contrary to the often outspoken mantra of equality. Because of that, some queer people, including Frank Vos, a queer activist co-founder of PATS and of ActUp Utrecht who also participated in the squatting movement in the 80s and 90s, did not feel at ease in the left-radical movement, until deep into the 1980s.

The left radical scene and queer people

Navigating between queer organisations and left-radical groups, it was not always easy to find your place, as summarised by Kaï Martchenova, a queer activist who worked and lived at the ACU in the 90s, in PATS #14 (1996):

In the COC they talk seriously about gay marriage. In the ACU I am the only dyke. [...] I like working in the ACU and the COC but I don't always feel at home, not in either place. The ideal workplace would be where a high percentage of dykes and faggots work and come up with progressive/left-wing radical ideas.

According to Kaï and Frank, the 1990s marked a turning point, where queer people were more accepted, but also felt more comfortable in the left-radical scene.

The ACU in the 1990s: becoming a radical queer space

Since the 1990s, the ACU has hosted an increasing number of queer events, which democratised its access for queer people. According to Kaï, this is in part because the place was then less linked to left-radical activism. This decade, for the queer community, is marked by the AIDS epidemic. Finding joy in being queer, celebrating it with other queer people, was at the time important, also because of this terrible epidemic.

However, in the 90s, the ACU was a hot centre for queer (radical) activism, hosting special nights of information, films or parties. In the Springstof zine #16 (1981), there is a special piece on the five-year anniversary of the ACU squat. This shows the central place of the ACU in Utrecht’s squatting and queer life, as it was known as a “flikkercafé” (“gay men café”, but “flikker” refers specifically to the activist/left-wing type of gay man), but also hosted “kraakspreekuren” (“squatting consultation hours”, information meeting about squatting with advice on how to squat a building, legal advice, etc.).

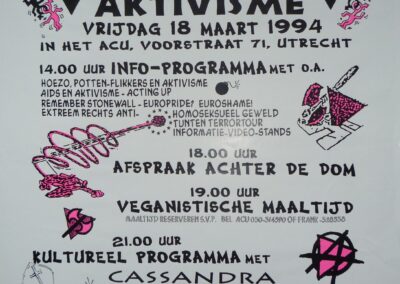

A concrete example of queer activism in the ACU was the themed-day “Gays and activism” in 1994, organised by the queer revolutionary fanzine PATS. During this day, the ACU hosted information meetings and debates by and about queer people and activism, with live music and vegan meals. As can be seen on the poster in PATS #5, there were discussions on aids and activism, or on the anti-gay violence of the far-right (p. 19).

Another important theme was the debate organised by Remember Stonewall around the EuroPride Amsterdam 1994. The radical activist organisation Remember Stonewall was not satisfied with the “apolitical and purely commercial approach of the organisation [EuroPride] in question” and planned to hold “its own alternative programme inspired by the events 25 years ago in New York during the Stonewall riots”, as can be read in PATS #6 (p. 11). In short, they rejected the liberal recuperation of pride, reminding that the first pride was a riot. As this themed-day exemplifies, the ACU was a vibrant place for radical-left activism in Utrecht, where the queers finally found their place.

The International Queer Liberation Tour (1995)

The queer people in the ACU were more internationally oriented than most other Dutch gays and lesbians groups from the same time period. If the COC also worked internationally, the international queer activism from the ACU differed in that it was at a grassroots level, corresponding to the anarchist ideal of the place. This is something also seen in the PATS, where queer news from all over the world could be found. Specifically in 1993 (from #3), the PATS introduced the “RG project”: an “international newsletter with information about the dykes’ and faggots’ fight as waged by alternative groups”.

“.

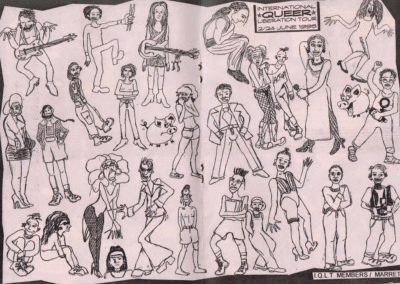

A great example of this international scope was the International Queer Liberation Tour (IQTL) of 1995. It was initiated by PATS, on a simple idea: put a lot of queers on a bus and ride across Europe, playing queer music and meeting other queer people. And they did it! Kicking off with a demonstration against homophobia in Utrecht (departing from the ACU, of course!), they went through Belgium, Germany, Czech Republic, Austria, Switzerland, and back to the Netherlands. The IQLT brought European queers together, through live music and protest.

Indeed, the idea was not only to have fun together, but also to “do some direct actions about the situation of queers in that particular country”, as explained in PATS #8 (p. 22). Calling on solidarity between queer people, the tour mixed activism and culture. In the PATS #11, a report of this International Queer Liberation Tour tells all about the solidarity between queers, and the local queer scenes in each country visited. It is notable that a lot of places where the IQLT took place were squats or former squats, showing the cultural entanglements of the queer and squatting scene throughout Europe.

The ACU today: a vibrant place for queer culture and activism

Nowadays, the time where Kaï was “the only dyke” in the ACU is long over. The place is known as a queer left-radical space, regularly hosting events such as drag makeup workshops, queer Dungeons and Dragons, or the Cruise Control queer party; Thursday vegan meals are also still going on. Alongside other former squats such as the Moira or Ekko, the ACU is a vibrant place of queer culture and queer activism to this day.

Justine Allasia

Sources

ACU. “About – Our story”. https://acu.nl/about [last retrieved 09/05/2025]

PATS

PATS #3 (Summer 1993)

PATS #5 (March 1994)

PATS #6 (May 1994)

PATS #8 (December 1994)

PATS #11 (September 1995)

PATS #14 (June1996)

Source: Queer Zine Archive Project (QZAP) https://archive.qzap.org/index.php/Detail/Object/Show/object_id/598 [last retrieved 09/05/2025]

Springstof

Springstof #16 (March 7, 1981)

Interviews by the author

with Frank Vos, October 16, 2024

with Marga Sutherland, November 13, 2024

with Kaï Martchenova, December 6, 2024

Illustrations

1. ACU in 1995. Fotodienst GAU; The Utrecht Archives, collection of visual materials.

2. Poster theme day “Gays and activism” in the ACU, 1994. Design by Oscar Bodelier.

3. Drawing celebrating the International Queer Liberation Tour 1995 in PATS #11.

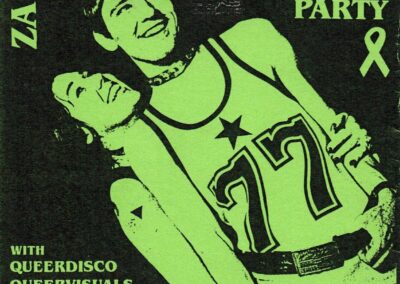

4. Poster for a queer party in the ACU on the occasion of the PATS good-bye party in 1999. Design by Oscar Bodelier.

5. The ACU in 2025, decorated for Koningsdag (Kings Day). Photo Justine Allasia.